It’s 1992 and fear has cast its unending shadow over the gay community in New York City. Reeling from a mysterious illness, a thirty year-old named John Patrick Dugdale lies on a metal bed in a cold and drafty hospital room. From afar, the scene is straight out of war-torn Beirut – but this battle is taking place inside Manhattan’s St. Vincent Hospital. Dugdale is not alone, for there are dozens of other young, frail men on the frontlines of death. It’s a dark moment for a city wrapped in the clenched fist of a virus called HIV/AIDS. This is where Dugdale’s journey to triumph begins to become one of New York most prominent master photographers.

Born in 1960 in the working class suburban town of Stamford, Connecticut, Dugdale dreamed of an artist’s life, “I thought of myself as being born in the wagon of a traveling van, just like the Cher song. I was a Guido, a real rough-around-the-edges kind of guy, raised by a big family who were right off the boat and could barely speak English. I had a dream of becoming one of greatest photographers of the 20th century.” Dugdale moved to New York City in his early twenties, enrolled at The School of Visual Arts and “got to know everybody” by waiting tables. New to the city, the very handsome, dark and dapper Dugdale was undaunted and quickly adapted to the limitless creative energy that engulfed the city. He began hanging with all the right people, in all the right spots like the Pyramid Nightclub. While still in the middle of art school, and still relatively untrained, friends of Dugdale approached him to shoot photographs for their flower shop, Madderlake. But unlike most starving artists, he first balked at the idea. “I didn’t want to do dull color photographs of flower displays,” he said. But after the owners promised him free artistic range and a sunny farm in upstate New York to shoot on, he gave it a try. As it turned out, it was the decision that would later help inspire him.

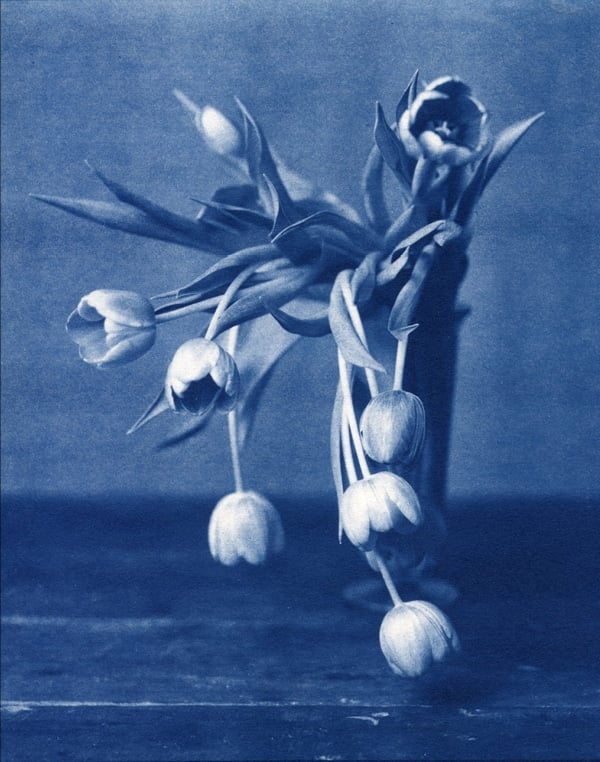

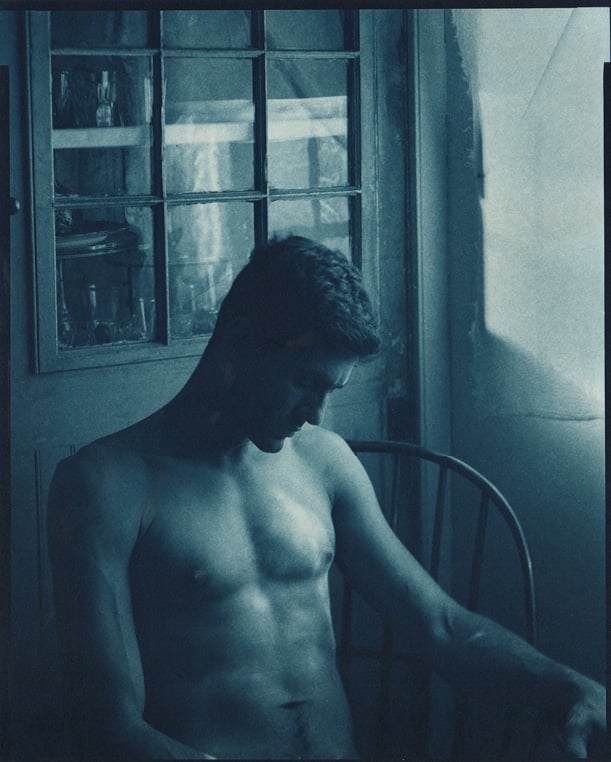

While on the farm shooting flowers, Dugdale’s creative energy took hold. He used the country surroundings to his advantage and transported himself into one of his favorite time periods, the 19th century. “I wanted to be very minimal, but not boring. I took one of those yellow bug lights and some panty hose that I borrowed from my performance artist friend John Kelly. I wrapped the panty hose over the light, which caused it to smolder and smoke, and it ended up giving the photographs a very Renaissance feel.” The reaction to his photographs was a smash, and Dugdale finally had a niche. He immersed himself in learning all types of vintage photography and film development, including coating his prints with egg whites and developing his photos using iron salts and sunlight to give his pictures a genuine rustic and blue-hue look. And that’s when the phone began ringing. “I was only 23 years old and I’d go into an editorial office to show them my work. They always thought I was some kid bringing in Mr. Dugdale’s book because they thought I was really a ninety year-old man.”

As fierce as the wind, Dugdale quickly became one of the ‘It’ photo boys, flying around the globe, making $30,000 a week; shooting supermodels but not necessarily shooting ‘art.’ Regardless, his work appeared in top publications like Cuisine, Connoisseur, The New York Times food page and wedding spreads for Bergdorf Goodman, Martha Stewart and Ralph Lauren. “I accidentally fell into a pile of gold just by faking it the entire time. I hit the scene just at the right moment. And boy did I think I had arrived – I would take breaks from shooting and go lean and pose on the studio wall outside so people could see me,” he said, laughing.

But just as he seemed unstoppable, a mysterious virus crept into his world. “I first learned about HIV/AIDS in the mid-’80s while I was waiting tables. A man in the restaurant was reading an article in The New York Times about a gay cancer, and all I could think was, “How could a cancer know if someone was gay or not?” But like a thief in the night, the virus struck him – Dugdale awoke one morning with a shortness of breath. For several months he fought off a half-dozen bouts of pneumonia. It got even worse the following year, in 1993, when again he woke up experiencing a massive and debilitating stroke. He was sent to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Greenwich Village and spent a year fighting for his life.

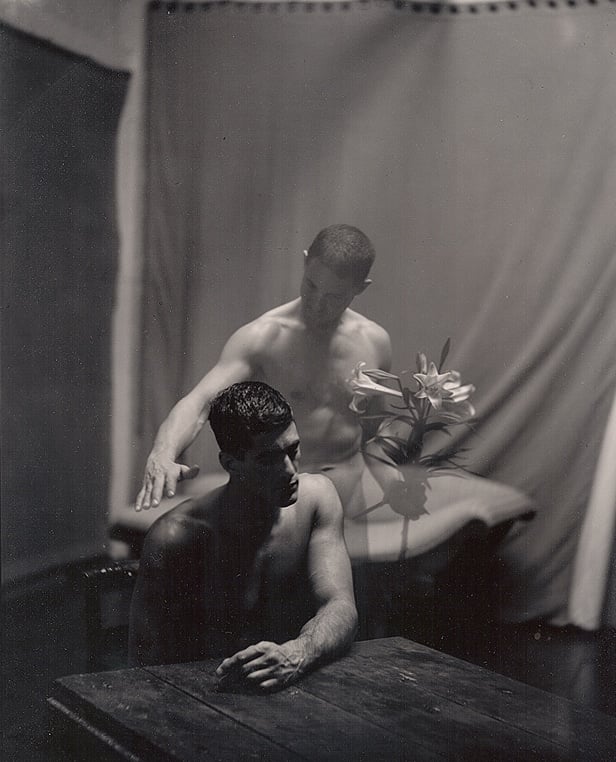

In the Shadow of his Beloved – 2001

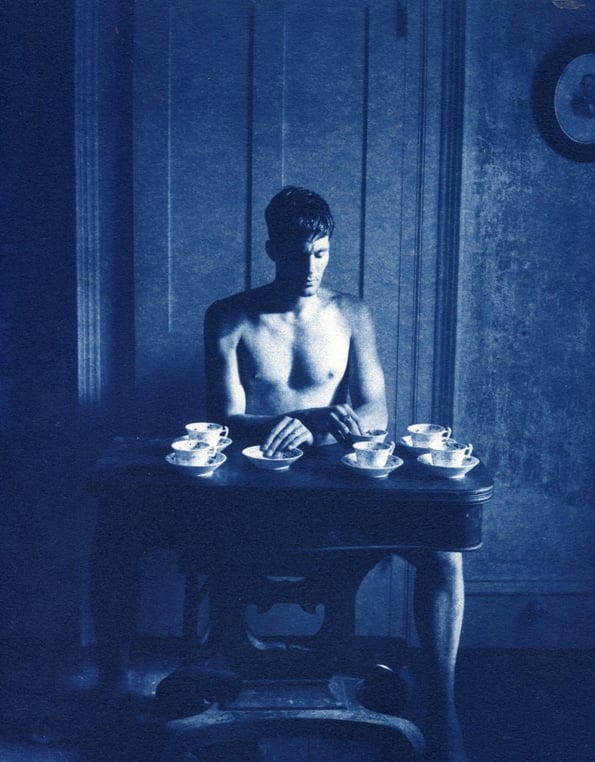

Cascade – Cyanotype Photograph – 1999

“My immune system got so low, that I got down to only four T-cells and I named them Winter, Spring, Summer and Fall, and similar to the seasons, I watched them all slowly fade away. I’d lie on the floor of St. Vincent’s and act as my own T-cells sometimes. I’d pretend I was General Patton and mentally order my T-cells where to go in my body. There were really no (AIDS) cocktails at the time so a lot of gay guys were trying holistic methods.” But his bravery wasn’t enough to stop the virus. Dugdale soon began losing his sight – another complication of the virus. “I went totally blind in my right eye and then had only a small sliver of vision remaining in my left eye. Back when I was sick my vision kept fading – it was like my moon waning. So I called my (remaining) sight my Crescent Moon.” Somehow, amidst the madness of disease, Dugdale found serenity and the courage to live while staying at St. Vincent’s. Dozens of sick patients got transferred into his shared hospital room, and seven souls on the other side of his curtain died. “I could always tell who was going to survive and who wasn’t by the tone of their voice. You could tell by what was coming out of their mouth. One friend would always pound on his legs and yell at his body for failing him… In the end he beat himself into dust.”

By some miracle, and with help from newly approved medications, Dugdale’s health improved dramatically, bringing him back from the edge of death. “I went back to my home in The Village; I was blind, half-paralyzed and walking with two canes. I refused a home aid worker because I didn’t want someone hanging out with me all the time. I wanted to do it my way. If I didn’t learn how to live, I knew I was gonna die. I would do laundry by climbing down the stairs on my butt with the basket on my back.”

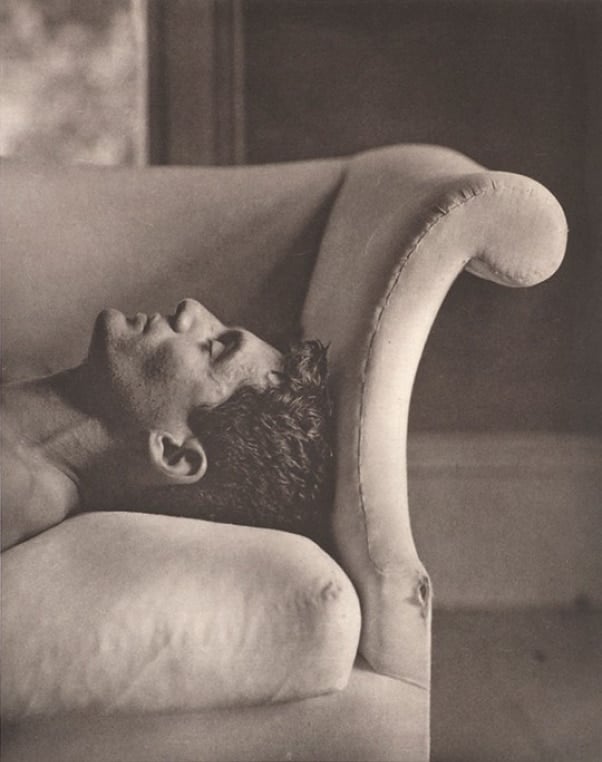

Long Enough, 2000

Nameless Lissisitude – 1999

Not long before returning home Dugdale received a life-changing phone call. His agent phoned with a job opportunity with Bergdorf Goodman. The agent, not sure what to tell the company, called up photographer Dugdale, hoping they’d be able to come up with some kind of lie or excuse. But instead the agent was shocked by Dugdale’s response. “I told them to tell Bergdorf ‘s, I’m HIV positive, I’m going blind and that I’m paralyzed from a stroke.” His pure honesty surprised even himself. “When that phone clicked, it was my release into freedom, a freedom of who I was meant to be.” High off his bravery, Dugdale called up an old gallery in Soho and set up an exhibit to showcase his experience of being ill. “While I was in the hospital I recorded all sorts of things – images, sounds, stories with a dicta-phone for inspiration. I thought my experience in the world of beauty and fashion and trying to perfect beauty on film served me well, because now I could express what happened to me in a way that wasn’t seen as horrific or gruesome.”

However, creating an entirely new exhibit for a show was an incredible challenge for Dugdale, as he had never photographed blind before. But like adapting to his illness, he found a new way to shoot. Using a static antique viewfinder camera, complete with bellows and cloth, he and his model would reverse roles. Dugdale would sit in a chair exactly where he wanted his model and pose as he wanted them to pose. Then he would order his model to do some focusing while Dugdale sat in front of the lens. “If you can tell that a TV is blurry, then you can tell if a photograph is in focus.” Once Dugdale was sure the moment was right, he would quickly get back behind the camera and snap his subject sitting in front of the camera. “I love the intimacy of photographing together; it makes for some really beautiful and revealing pictures – an experience we share together.” To Dugdale, a revealing photo meant ridding the self of clothing, being totally nude. “Life is transient. Once you leave this world, you fly into the universe without clothes. I want people to learn you cannot protect yourself by hiding behind clothes.”

Healing and sharing his experience was the main reason for Dugdale’s desire to create a new body of art. “I wanted to show the essence of what it was like to be a human being. When I got out of the hospital, I didn’t want to show all the horrifying things that I went through, like going paralyzed, having seizures, and almost swallowing my tongue. I wanted to show the beauty of life and how one should act around illness.” In one photograph, Dugdale summoned a muscular male dancer friend. “Instead of showing a frightening picture of my final seizure, I had my muse remove his clothes, and pose as if he was having a seizure. Without thinking, he lay on his back and put his arms and legs in the air. I was struck by the pose, so we looked up the word seizure in the dictionary and it was defined as ‘a sudden taking.’ The image was exactly perfect.”

Thoughts – 1999

Thoughts – 1999

“Lengthening Shadows Before Nightfall” was the name of his exhibit, and it was ready in less than six months after his hospital release. A crowd of people – many whom he thought had forgotten about him – lined Thomas Street in SoHo for a glimpse of his work. Inside, onlookers found his blue-hued photographs of delicate naked bodies and images covering the gallery’s ghost-white walls. It was a collection of forty photos of self-portraits and loved ones. It was his autobiography in pictures, a reflection of his life and survival. Friends who had just checked out of St. Vincent’s arrived still wearing their hospital gowns and took in the exhibit alongside rich celebrities, weeping over his photographs. “This was the real birth of me as an artist. And I got here in a way that I never expected. If someone would have told me how I’d get to this moment, I would have fled in horror.” When the show ended and every photograph was sold and taken home, Dugdale sat on the floor in the middle of the gallery, head between his knees, and cried uncontrollably.

Dugdale’s is now considered a New York master photographer, featured in nearly 200 galleries and art exhibits around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Whitney Museum, and Miami Art Museum. In 2010, Dugdale created The John Dugdale School of 19th Century Photography and Aesthetics. It sits inside an 1850’s ‘Beatrix Potter’ type house, on a twelveacre corn field in upstate New York. He bought the house years before, when it was decaying and pockmarked with rabbit holes. The landscape that inspired him years ago while photographing flowers now serves as an inspiration to his students. And his syllabus is centered on the four seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. In late 2013, he hopes to start more apprenticeships, so he can create more original art.

John Dugdale has been completely blind for several years, and is proud to now have five hundred and twenty T-cells and be healthy. He is a charming man, who still has a boyish excitement when talking about his art and life. And although he walks with the aid of his seeing eye dog – a big, lovable English labrador named Manley – he possesses a certain quiet confidence. “People often tell me they feel sad that I have no sight. But I tell them, it would have been much sadder if I were wearing my grass carpet right now. I got to live out my dream without my sight, and it seems like it was supposed to happen that way. I don’t wait for some cure to come, because if I did, I would have missed out on everything, just sitting and waiting. Someday, I think my face is going to start hurting from smiling so much.”•

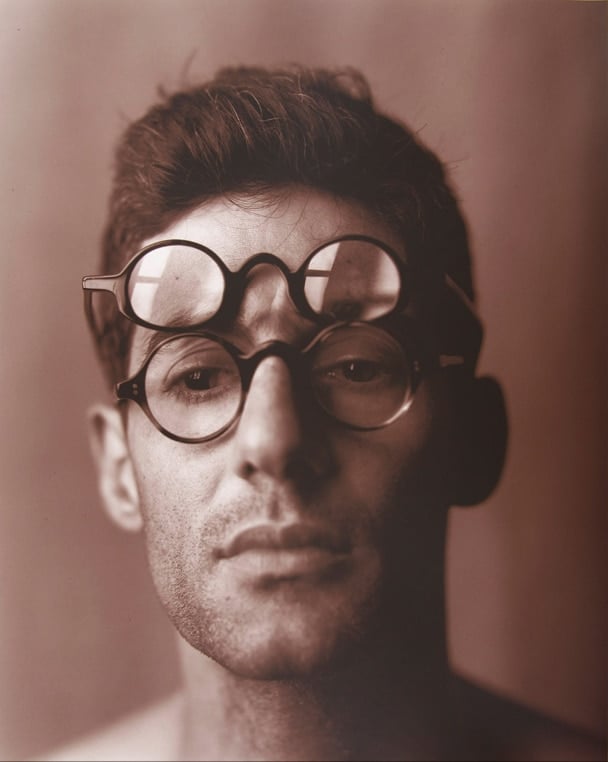

Spectacle – 2010